'What The Fish' And Social Media Sushi

Why isn't the New York Times writing about this bar that serves Dominican sushi. Is it because it's kitschy without being self aware? Fuck off

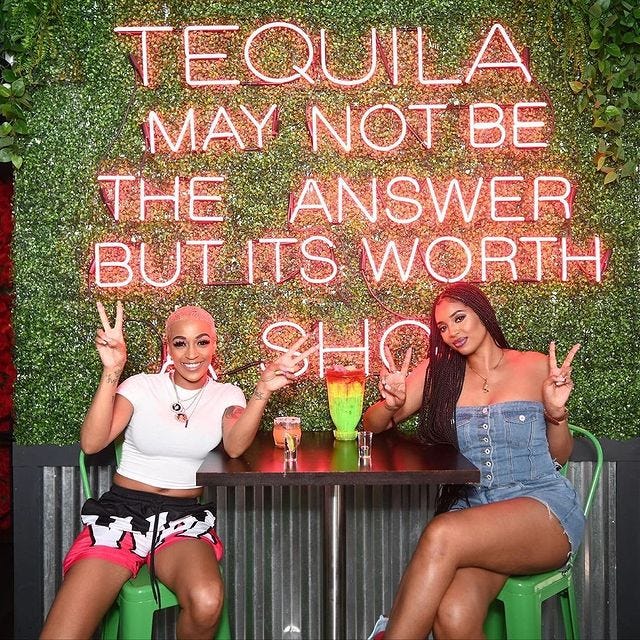

You can tell when Robert Perez buys a restaurant near you because one day, without warning, there will be a giant neon sign in there. For example, after Robert bought Barrio, a taqueria near Astoria Kaufman Studios, it donned a sign that takes up about a third of its backwall. It reads, “TEQUILA MAY NOT BE THE ANSWER, BUT IT’S WORTH A SHOT.”

Robert, the owner of several restaurants in the Astoria/Long Island City area, recently opened up his most ambitious venture yet: What The Fish. It’s a sushi lounge and nightclub that carries Carribean-inspired Japanese cuisine— advertised as “Asian Latin Fusion” on Google Maps. When I learned about this combination, I was determined to stop by and see how exactly the kitchen managed to pull this off, and why.

What The Fish has at least five neon signs inside, with phrases ranging from “This is how we roll!” to “We’re all mad here.” The place is bumping with reggaeton and other club genres, and it feels like it’s late at night inside even at 5pm. When I sat down with Robert to ask him about the restauarant’s theme and recipe development, he gave me a singular take-home message. It doesn’t really matter where the restaurant’s at, or even what it serves. Presentation, he said, was how to guarantee repeat customers at a restaurant.

Although Robert assured me he cares about quality food, he thinks it just isn’t enough to sustain a restaurant on its own. “People like food. But if the picture isn’t good enough to post, they won’t come back,” he said.

Pepperoni Pizza sushi rolls featured on the What The Fish instagram.

I asked Robert about his relationship to Japanese culture. He said he was from the Domincan Republic (he was wearing a hat that said “Colombia” on it). I asked who designed the menu, and he said he did it himself. I asked who designed the look of the restaurant, and he also credited it to himself. He was shy enough to not want to be recorded, or our interview to be published in any official outlet. But not too shy to stop encouraging me to take pictures. He kept bringing out plates of elaborate sushi and cups of something called a “Thai Cocolada.” I was trying to stay objective, and not get so drunk on orientalist margaritas I couldn’t write the most insightful and biting piece on sushi of the next century. Sadly, our goals were fundamentally at odds.

Robert asked me if I was an influencer. Because I was interviewing him for a free online food writing class, said I was a “journalism student.”

“Why?” he asked. “Influencers get way more perks. Free food, everywhere they go. You’d get more out of it.”

I felt out of place. Everything was designed for a social media personality to smile at, not for a journalist to inquire about. Where was the thematic depth within the “Fireball” meatball roll? Or the campy play-on-kitsch provided by the “Asian honey shrimp” cheekily served in a Chinese food takeout container?

I sat there, unable to continue refusing his delicious gifts, and gave up trying to conduct an ethical interview with journalistic integrity. What was the point? Robert didn’t seem to care at all that I might write a thoughtful review of his restaurant, or that I might analyze the meaning of Dominican stewed pork and spicy tuna existing together inside a hand roll. After all, the ingredients in the sushi didn’t delicately intermingle, they crashed against one another. My taste buds were in a tiny wooden boat, trying to row through some sort of flavorful tempest, overwhelmed by its power and muscle.

I soon became terribly drunk on an enormous fruity cocktail (with an entire popsicle dipped inside), thoughts of food social media content swirling in my head.

I don’t really know what I’m doing with my life right now. Every career path seems like an equally valid possibility—professional journalism, internet opining, or heart surgery—and I’m completely overwhelmed. Why call a sushi roll “cookie monster” and put coconut flakes on it? Why does anyone do anything?

I don’t know if it’s particularly nihilistic to make sushi rolls that have names like “Beach Body” and contain plantains. Making things geared towards social media audiences isn’t ontologically evil and nobody is “better than” enjoying them. Do I have to be a professional journalist with professional taste to be happy sharing what I love?

What the Fish’s food was built to be eaten through a screen just as much as through a mouth.* The background of the food isn’t important, and it certainly can’t afford to be subtle. As an established gremlin, I loved the umami of huge flavors clashing together in all their zealous glory. But as a coastal elite, I felt intellectually left out. Other professional writers seemed to be too. Only a few in local Astoria outlets left reviews for What the Fish after it opened. But on social media, What the Fish brings in new influencer content weekly.

Despite knowing socials-baiting repels established press, there are a lot of restuarants in my area that seem to agree with Robert’s formula for success.

*A lot of things that were once made for only the most selective of artists now can have a social media bent: see also Instagram “museums.”

In Astoria, for every one restaurant that could get a feature in The New York Times or Eater, there are probably twelve that just sorta popped up with no fancy chef to their name, slinging classic hits or strange reinventions without any cohesive narrative. But I love those places, even though they’re not intentionally engaging with the food world conversations that get published to the magazine-reading crowd.

Sushi is very susceptible nowadays to being generally vibeless, as anything that is sold in 7-11 can be. There are 1,001 takes on sushi that don’t merit much of a higher discussion, no matter how unusual or flashy. Sushi has been beaten to death by fusion. Its link to Japanese culture can be as non-existent as the presence of actual fish in a roll.

These combinations feel cynical—completely disconnected from any reverence for the origins and art of sushi. But also, they’re weird as all hell, and people like them. What the Fish seems to sit squarely on the line between just another hacky take on sushi and something strange enough to be genuinely interesting. And it should be worth saying—the food was good.

While I try to figure out if food writing could be a part of my career, I’m thinking a lot about the difference between local foodies, who find and amplify cool spots, and food reporters, who synthesize trends and dissect cuisine. Usually, foodie influencers are the ones that alert food journalists to ideas or businesses that have the potential to be a story in the first place.

But not every restaurant will be seen as noteworthy to the academic and exclusive institutions I have learned to trust and respect. And some restaurants don’t want to be in the influencer world, either.

Righteous Eats, one of my favorite social media food creators, speaks about being rejected from making videos with high-end restaurants.

Are social media influencers nothing more than an advertising machine made up of distracted chumps, with little ethical oversight? I’d like to believe they can provide genuine organic, even democratic (to the extent that social media platforms can allow) cultural exchange and community. I also think if I see another cheese pull or butter board, I’ll die!

Social media foodies encourage restaurants to think bigger, not deeper, about what’s possible within a restaurant. But their culture has changed the real world to start reflecting our online desires. Social media feels like a “place,” with a unique culture and aesthetic that frequent travelers try and reproduce in their real-world homes and businesses. Cross too many things over, and it starts to look like a blur. But blurry is the perfect thing for a nightclub to be, frankly.

Restaurants like What the Fish feel like subconscious melanges of aesthetics, semiotics, and fetishism. It went wrong when German Doner Kebab made a “cheesy doner box” out of beef, pickled jalepeño slices, and gluey nacho cheese. But sometimes thinking way less than you should is the artist’s job. And it’s the job of the writer to try and make it all make sense.